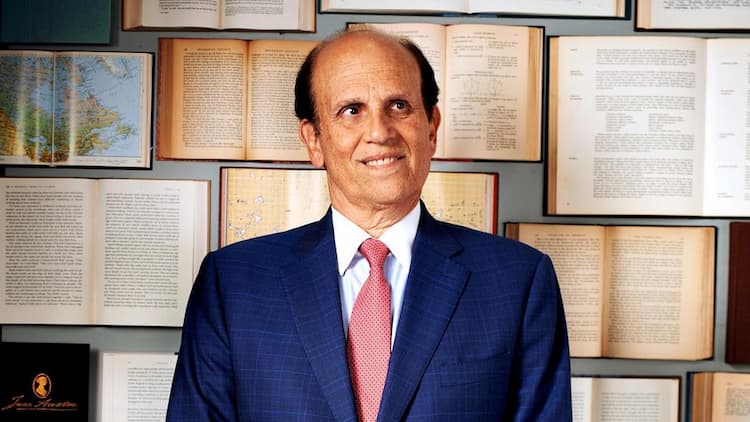

Michael Milken Biography

Michael Milken is a philanthropist and financier from the United States. He is well-known for his role in the development of the high-yield bond market (“junk bonds”), as well as his conviction and sentence following a guilty plea on felony charges of violating US securities laws.

How old is Michael Milken? – Age

He is 76 years old as of 4 July 2022. He was born in 1946 in Encino, Los Angeles, California, United States. Her real name is Michael Robert Milken.

Michael Milken Family – Education

Milken was born in Encino, California, to a middle-class Jewish family. He graduated from Birmingham High School, where he was the head cheerleader and worked at a diner while in school. Future Disney President Michael Ovitz, as well as actresses Sally Field and Cindy Williams, were among his classmates. He received his B.S. with honors from the University of California, Berkeley in 1968. He was a member of the Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He earned his MBA from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Michael Milken Wife

Lori Anne Hackel, whom Milken dated in high school, is his wife. The couple has three kids.

Michael Milken Net Worth

He has an estimated net worth of around $3.7 billion. Forbes magazine ranks him as the 606th richest person in the world.

Michael Milken The junk Bond

Milken was one of the merger’s few notable holdovers from the Drexel side, and he became the merged firm’s head of convertibles. He persuaded his new boss, fellow Wharton alumnus Tubby Burnham, to allow him to establish a high-yield bond trading department, which quickly earned a 100 percent return on investment. Milken’s salary at the firm, which had become Drexel Burnham Lambert, was estimated to be $5 million per year by 1976. Milken relocated the high-yield bond operation to Century City in Los Angeles in 1978.

By the mid-1980s, Milken’s network of high-yield bond buyers (particularly Fred Carr’s Executive Life Insurance Company and Tom Spiegel’s Columbia Savings & Loan) had grown to the point where he could quickly raise large sums of money. This ability to raise funds also aided the activities of leveraged buyout (LBO) firms such as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and the so-called “greenmailers.” The majority of them were armed with a “highly confident letter” from Drexel, a tool devised by Drexel’s corporate finance wing that promised to raise the necessary debt in time to meet the buyer’s obligations.

It had no legal standing, but by this point, Milken had established a reputation for being able to make markets for any bonds he underwrote. As a result, “highly confident letters” were thought to reliably demonstrate the capacity to pay. Supporters, such as George Gilder in his book Telecosm (2000), claim that Milken was a genius “a significant source of the organizational changes that have propelled economic growth over the last two decades Most notable was the capital productivity surge, as Milken… and others redirected vast sums trapped in old-line businesses back into the markets.”

Martin Fridson, formerly of Merrill Lynch, and author Ben Stein are two of his most vocal critics. Milken’s status as a high-yield “pioneer” has been called into question, as studies show that “original issue” high-yield issues were common during and after the Great Depression. According to Milken, high-yield bonds date back hundreds of years, having been issued by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century and America’s first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Others, including Stanford Phelps, an early associate and rival at Drexel, have disputed his claim to have invented the modern high-yield market.

Michael Milken SEC

The SEC announced in February 2013 that it was investigating whether Milken violated his lifetime ban from the securities industry. The probe centered on Milken allegedly providing investment advice through Guggenheim Partners. The SEC has been looking into Guggenheim’s relationship with Milken since 2011.

Michael Milken Sentence

A federal grand jury indicted Milken on 98 counts of racketeering and fraud in March 1989. The indictment accused Milken of a slew of wrongdoing, including insider trading, stock parking (hiding the true owner of a stock), tax evasion, and numerous instances of illegal profit repayment. According to one charge, Boesky paid Drexel $5.3 million in 1986 for Milken’s share of illegal trading profits. This payment was billed to Drexel as a consulting fee. Shortly after, Milken left Drexel to start his own firm, International Capital Access Group.

Milken pleaded guilty to six counts of securities and tax evasion on April 24, 1990. Three of them involved transactions with Boesky in order to conceal the true owner of a stock. The final charge was a conspiracy to commit these five violations. Milken agreed to pay $200 million in fines as part of his plea deal. Simultaneously, he agreed to a settlement with the SEC in which he agreed to pay $400 million to investors who had been harmed by his actions. He also agreed to a lifetime ban from working in the securities industry. He agreed to pay $500 million to Drexel’s investors in a related civil lawsuit. Critics accuse the government of indicting Milken’s brother Lowell in order to put pressure on Milken to settle, a tactic that some legal scholars condemn as unethical.

The case against Lowell was dropped as part of the agreement. Federal agents questioned some of Milken’s relatives about their investments as well. In 1991, Judge Wood told a parole board that the “total loss from Milken’s crimes” was $318,000, less than the government’s estimate of $4.7 million, and she recommended that he be eligible for parole in three years. Milken’s sentence was later reduced from ten to two years, and he served 22 months.